[ad_1]

The only HIV vaccine in a late-stage trial has failed, researchers announced Wednesday, dealing a significant blow to the effort to control the global HIV epidemic and adding to a decadeslong roster of failed attempts.

Known as Mosaico, the trial was the product of a public-private partnership including the United States government and the pharmaceutical giant Janssen. It was run out of eight nations in Europe and the Americas, including the U.S., starting in 2019. Researchers enrolled nearly 3,900 men who have sex with men and transgender people, all deemed at substantial risk of HIV.

The leaders of the study decided to discontinue the mammoth research effort after an independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed the trial’s findings and saw no evidence the vaccine lowered participants’ rate of HIV acquisition.

“It’s obviously disappointing,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, who as the long-time head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) was an integral partner in the trial, said of the vaccine’s failure. However, he said, “there are a lot of other approaches” early in the HIV-vaccine research pipeline that he finds promising.

“I don’t think that people should give up on the field of the HIV vaccine,” Fauci said.

Fauci previously said he did not want to retire from the NIAID until an HIV vaccine had been proven at least 50% effective — good enough, in his view, for a global rollout. Instead, he retired from his post at the end of last month with this dream unfulfilled.

In addition to NIAID and Janssen, which is a division of Johnson & Johnson, the trial was run by the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, which is headquartered in the Fred Hutchinson Research Center in Seattle, and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command.

Mosaico’s lack of efficacy was not unexpected, experts said, because of the recent failure, announced in August 2021, of a separate clinical trial, called Imbokodo, which tested a similar vaccine among women in Africa. Between the two trials, NIAID spent $56 million, according to an agency spokesperson.

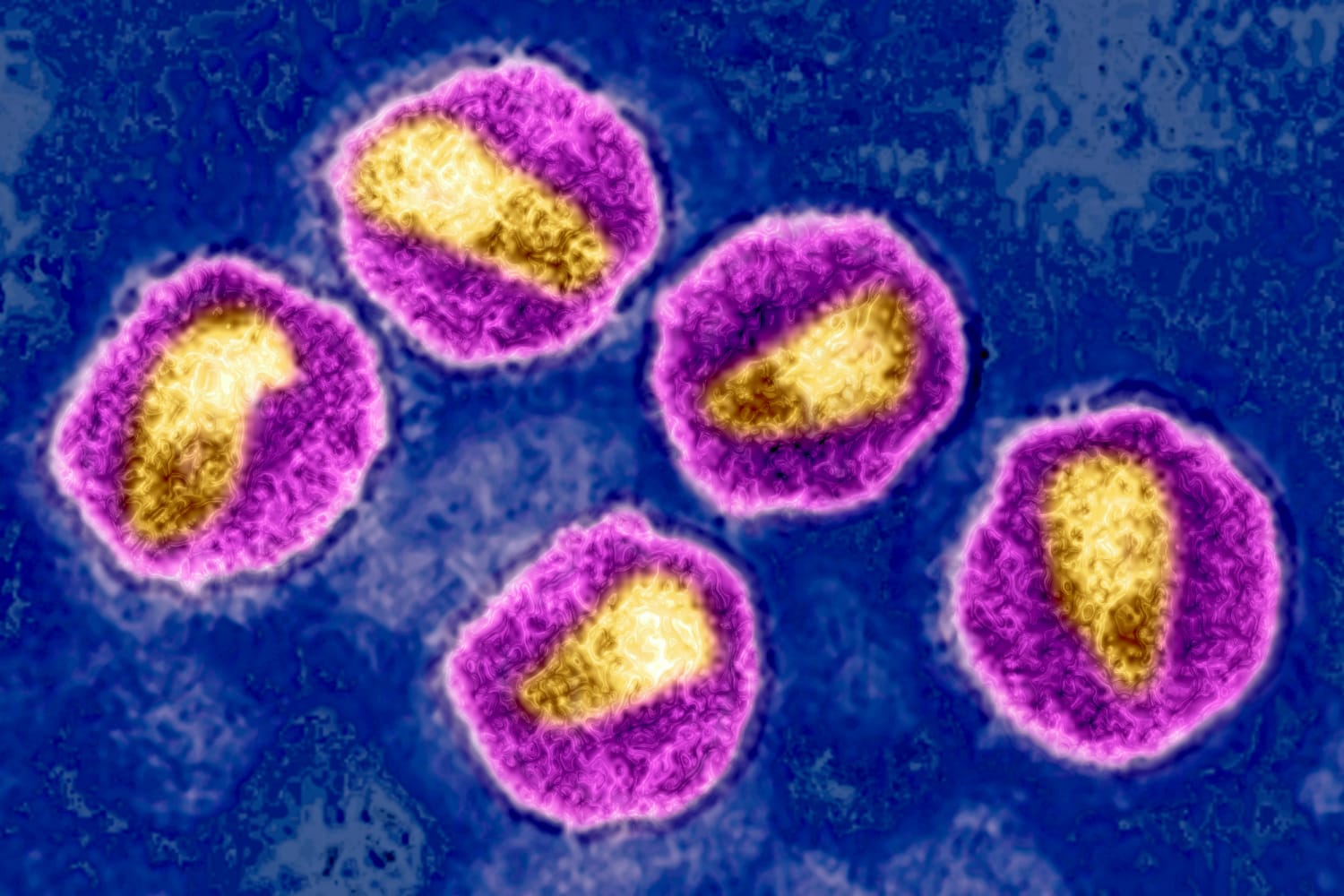

The vaccines tested in both trials used a common cold virus to deliver what are known as mosaic immunogens, which were intended to trigger a robust and protective immune response by including genetic material from a variety of HIV strains prevalent around the world, according to the National Institutes of Health. Mosaico included an additional element intended to broaden the immune response.

Participants in Mosaico, who were between ages 18 and 60, received four injections over 12 months, either of the vaccine or a placebo. The monitoring board found no significant difference in the HIV acquisition rate between the two study groups.

Fauci said that a critical limitation of the Mosaico vaccine was that it elicited what are known as non-neutralizing — as opposed to neutralizing — antibodies against HIV.

“It is becoming clear,” he said, “that vaccines that do not induce neutralizing antibodies are not effective against HIV.”

Up-and-coming HIV vaccine innovations, including efforts that rely upon the cutting-edge mRNA vaccine technology behind some of the coronavirus vaccines, may hold the key, Fauci said.

The critical problem that has bedeviled HIV vaccine research for decades, Fauci noted, is a crucial weakness that the virus already successfully exploits: The natural immune response to infection is not sufficient to thwart the virus.

“So vaccines would actually have to do better than natural infection to be effective,” he said. “That would be a very high bar.”

A decadeslong effort

In 1984, following the discovery of HIV as the cause of AIDS the previous year, President Ronald Reagan’s health secretary, Margaret Heckler, famously claimed a vaccine for the virus would be available within two years.

In the decades since, there have been nine late-stage clinical trials of HIV vaccines, including Mosaico and Imbokodo, plus one, called PrEPVacc, that is still underway in Africa. However, the vaccine in PrEPVacc is not considered to be on a direct path to licensure if it demonstrates efficacy. Only one of these vaccines has shown any efficacy — and only at a modest level, not considered robust enough for regulatory approval — in a trial conducted in Thailand between 2003 and 2006, the findings of which were published in 2009.

In the years since, a phalanx of global researchers has studied the Thai trial in hopes of developing insights to inform further HIV-vaccine development.

The yearslong effort to design the Imbokodo and Mosaico vaccines was in part grounded in an attempt to build on the modest success of the Thai trial.

“We had hoped that we would see some signal of efficacy from this vaccine,” said Dr. Susan Buchbinder, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who co-led the Mosaico trial. She added that, promisingly, as in the Imbokodo trial, there were no evident concerns about the vaccine’s safety.

Buchbinder said it is too early to determine the reasons behind the Mosaico vaccine’s failure. Her team will be analyzing blood samples from participants over the coming months to investigate. They will also seek to determine if there were any subgroups of participants among whom the vaccine did show any efficacy. As with the Thai trial, the hope is to channel research findings into future HIV vaccine development.

Other HIV prevention tools

Jennifer Kates, director of global health and HIV policy at Kaiser Family Foundation, said the trial’s failure is a “stark reminder of just how elusive an HIV vaccine really is and why this kind of research continues to be important.”

“Fortunately, there are a number of highly effective HIV prevention interventions already,” Kates added. “The challenge is to scale them up to reach all at risk.”

Pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, in which people at risk of HIV take antiretroviral medications in advance of potential exposure to the virus, is highly effective at preventing infection but remains vastly underutilized in the U.S. and around the world.

Additionally, research published in the mid-2000s showed that voluntary medical male circumcision lowers the risk of female-to-male HIV acquisition by about 60%. This led to a major effort to promote circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa, home to two-thirds of the HIV cases in the world.

In more recent years, an antiretroviral-infused vaginal ring has proven effective at lowering women’s HIV risk. Initial efforts are underway to introduce it in African nations.

And, of course, there is the old mainstay: condoms.

Globally, an estimated 38.4 million people were living with HIV in 2021, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Some 1.5 million people currently contract the virus annually, a figure that has more than halved since its peak in 1996.

It is at least theoretically possible, although extremely challenging, to bring HIV to heel without a vaccine. Fortunately, successfully treating HIV eliminates the risk of transmitting the virus through sex. So HIV transmission has declined in recent years in large part because of the dramatic scale-up of antiretroviral treatment of the virus, which by 2021 reached 28.7 million people.

Mosaico was particularly challenging to design ethically because of the advent of PrEP, which was first approved in the United States in 2012. To prove a vaccine works, researchers must recruit participants who remain at substantial risk of HIV over time. So Mosaico first offered PrEP to those seeking to enroll in the trial and only accepted as participants those who adamantly declined the preventive therapy notwithstanding their risk of HIV.

[ad_2]

Source link