[ad_1]

The 16-hour of torrential rainstorm that straddled the night of September 7th and the morning of 8th not only plunged various districts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) into chaos, but also raised serious questions on what lessons the government should learn in dealing with sudden crisis management.

At 9.25 pm on September 7th, the Observatory issued a yellow rainstorm alert. Two minutes later, the alert was changed to a red one. At 11.05 pm, black rainstorm warning was issued.

At 12.15 am on the morning of September 8th, the MTR Corporation announced that the line between Kwun Tong and Whampoa terminated service.

Hong Kong’s media have revealed that the Observatory sent separate warnings to government departments on the night of September 7th, including fire services, police, and the drainage department, on the possible scope of damage incurred by the rainstorm.

Then department officials held meetings to produce their contingency plans, just like the past experiences during which typhoons attacked Hong Kong. After the midnight when 158 mm (6.2 inches) of rainfall poured into the HKSAR within an hour – a historical phenomenon since 1884 – it was reported that Chief Secretary Eric Chan met with departmental officials to prepare the mobilization of manpower and resources to cope with the crisis.

At around 1.19 am on September 8th, the Facebook of Chief Executive John Lee asked the residents to stay in safe places and it said the government was making all the efforts to deal with the torrential rainfall.

At 5.34 am, the government announced that, due to severe weather, day and night schools would terminate their classes, while employers would deal with their work arrangements in accordance with the practices under Typhoon number 8 conditions.

The severe weather condition lasted until 12 am on September 9th.

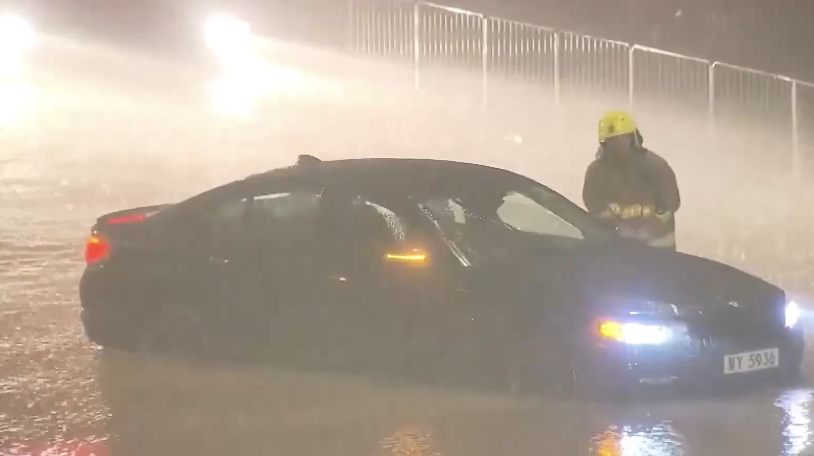

The rainstorm brought havoc to many districts: Temple Mall North in Wong Tai Sin was flooded with muddy water; Shau Kei Wan witnessed flooding and severe damage on its roads; the MTR station in Wong Tai Sin was badly damaged; citizens were trapped in cars many of which were stranded and damaged; at least 151 trees were fallen; 39 landslides took place; 20 schools reported their facility damage; 144 residents needed hospital treatment; 343 calls were made to the government for assistance; and at least 335 people took refuge in temporary shelters in the North district.

On September 9th, Chief Secretary John Lee met the media, and he agreed that a review should be undertaken to see whether the warning system can be improved further.

With the benefit of hindsight, the government could have done better even though the torrential rainfall in a short period of time was regarded as once in 500 years.

First and foremost, the warning given to residents by the government was too late, unlike the situation during the Super Typhoon Saola during which the government hoisted Typhoon number 8 much earlier for citizens to have sufficient time to buy food and make precautionary measures at their homes. Indeed, the speedy movement of Saola might be a fortunate event that could minimize the damage done to the HKSAR.

However, interestingly, the torrential rainfall caused by Typhoon Haikui, which had made serious landfall in Fujian province, should have alerted the officials of Observatory much earlier. Mainland news on September 5 and 6 had already reported the severe damage incurred by Haikui as it moved south from Fujian to Guangdong. Based on proper weather intelligence-gathering and analyses, the Observatory should have alerted the government departments and residents much earlier instead of raising the yellow rainstorm alert to black one within one and half hours on the night of September 7th. Indeed, the Observatory officials explained on the afternoon of September 8th that it was more difficult to predict the movement of rainstorm. Critically speaking, technological predictions might be “difficult” in situation of rapid climate change, but earlier intelligence analyses of weather conditions and Haikui’s movement could increase the level of the rainstorm alert much earlier.

Second, even though the Chief Secretary coordinated the departments concerned quickly to cope with the rainstorm, the Hong Kong media have accurately pointed to the inadequacies of governmental communication with the public. Some media and critics have pointed to the need for the government to use the SMS system to alert the residents of the rainstorm situation. Yet, one official told the media that such SMS alert could have scared the residents during their sleep – a remark that could be regarded as apparently convincing but controversial. The question was what time a proper message should and could be used through SMS to alert the residents of the dangers of the rainstorm. In any case, the Emergency Monitoring and Support Centre supervised by the Security Bureau and the cross-departmental steering committee led by the Chief Secretary should perhaps study how earlier warning signals would be improved in the future, especially when climate change would very likely produce natural disaster of a similar kind through sudden rainstorm attack.

Third, it was reported that Shenzhen informed the HKSAR authorities sixteen minutes before it decided to discharge its reservoir waters, but the Hong Kong government later clarified that it had been informed 45 minutes earlier. Objectively speaking, the crisis made it difficult for the Shenzhen authorities to inform their Hong Kong counterparts earlier, but more cross-border governmental communications will be necessary to enhance mutual dialogue and mutual alert in case of sudden rainstorm attack. The torrential rainstorm caused havoc in not only Fujian, but also Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong – evidence pointing to the detrimental force of the so-called “residual rain” caused by Haikui.

A minority of Hong Kong residents raised the question on whether the Shenzhen water discharge might have exacerbated the flooding in the New Territories – a claim without evidence indeed. Interestingly, a pro-Beijing daily in the HKSAR on September 9th criticized such a “big rumour” as irresponsible and it interviewed a weather expert who insisted that the flooding in Hong Kong had no relation with the Shenzhen water discharge. Objectively speaking, ordinary citizens were not weather experts, but it was up to the government authorities to communicate with citizens in a better and prompt manner to dispel such an unfounded rumour.

Fourth, some lawmakers have pointed to the need for the government to examine its announcement on the morning of September 8th that employers should make their own work arrangements. While the government said that it could not “cut in one slice” by asking all employees to stop their work, trade unionists have argued that there was a “legal vacuum” by asking employees to do so. Federation of Trade Union legislator Tang Ka-piu said that there should be a legislation on the termination of work, and that employers and employees do not really know how to respond to the government’s call for them to arrange their own work under “severe weather” conditions. Other critics of the government said that it kicked the ball to employers to deal with a crisis without clear guidelines. It is controversial on whether the government should legislate on the termination of work under “severe weather” condition or whether it should just issue guidelines to do so. Currently, the government believes that employers should be given the discretion to decide work arrangements under the circumstances of Typhoon number 8.

In conclusion, the torrential rain caused by the “residual rain” of Haikui exposed the problems of crisis management in the HKSAR. Earlier weather warnings could have been made; better communications with the citizens could also have been made; more communication is also needed between the Hong Kong and Shenzhen government authorities in dealing with weather and climate change; and there is a need for review of the discretion given to employers in work arrangements under Typhoon 8 circumstances. If national security embraces how governments deal with sudden climate change conditions, then the HKSAR authorities must learn a lesson from the legacies of the sudden and heavy rainstorm that brough havoc to Hong Kong within a short period of time.

*Sonny Shiu-Hing Lo is a political scientist, veteran commentator, and author of dozens of books and academic articles on Hong Kong, Macau, and Greater China

[ad_2]

Source link