Hong Kong’s economy has undergone significant structural changes since the early 1980s, becoming one of the world’s most service-oriented economies. While the service sector accounted for more than 93 per cent of gross domestic product in 2020, the share of manufacturing stood at a mere 1 per cent, a far cry from the 23 per cent recorded in 1980.

The significant

decline in manufacturing and heavy reliance on the service sector has led to an imbalance in Hong Kong’s industrial structure and a narrow economic base.

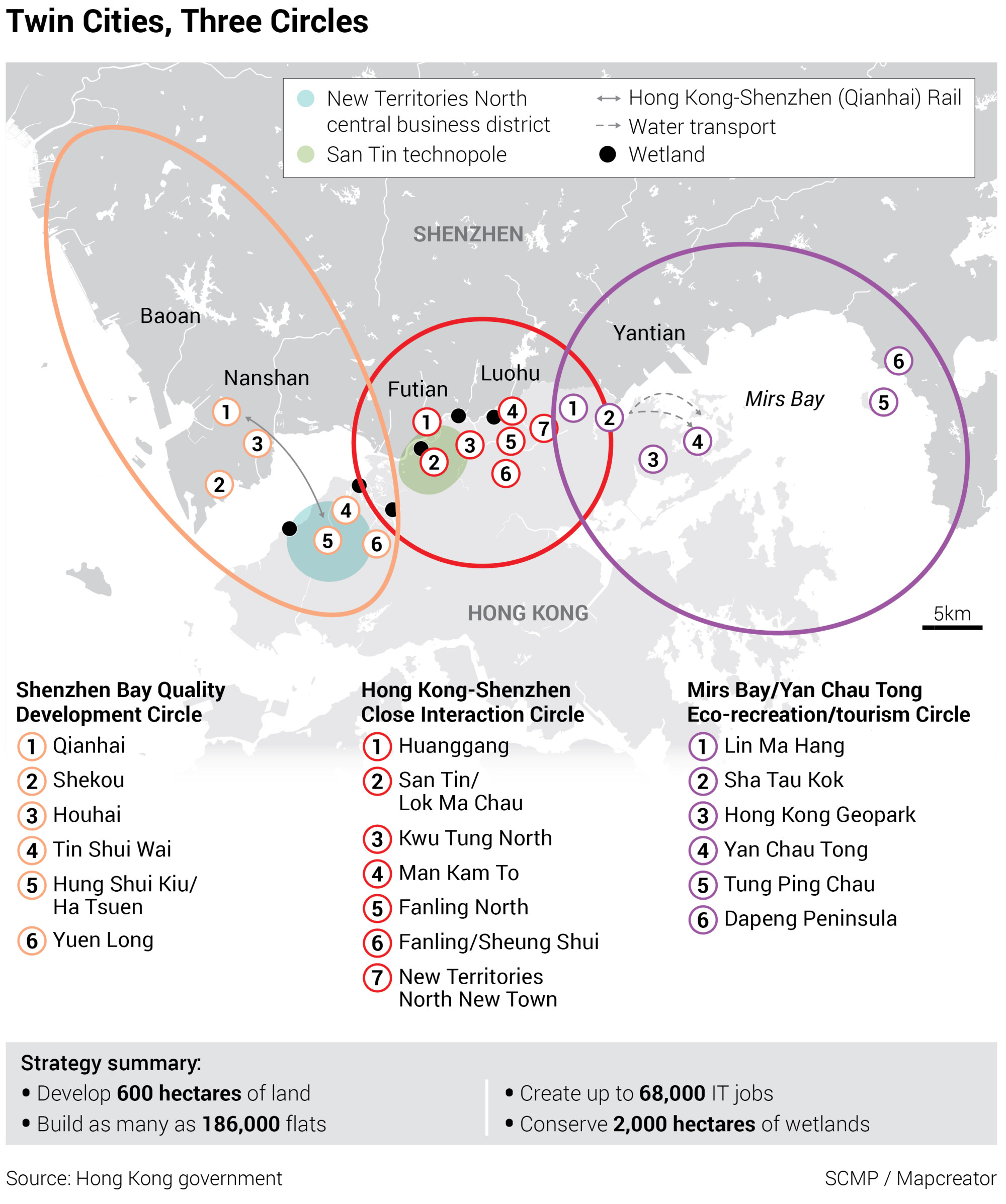

To reverse this trend, the government has laid out a clear policy intention to develop the innovation and technology (I&T) industry in Hong Kong, with the

San Tin Technopole at the heart of this vision. Providing 300 hectares of land, the flagship project will cover 7 million square metres (75.3 million square feet) of gross floor area for I&T uses and is expected to create more than 120,000 jobs.

However, it would be a gross oversimplification to assume that infrastructure alone can yield the desired outcome. Making the San Tin Technopole a success will require shifts in our approach to development, attracting investment and land allocation. Only when both the hardware and software are in place can Hong Kong be ready to build a vibrant and thriving

I&T ecosystem.

Public-private partnerships for infrastructure projects are not new. Take the case of Sha Tin: while the government took up the major land assembly, the private sector was brought in to carry out reclamation and site formation works. On completion, 70 per cent of the reclaimed land reverted to the government for public housing and infrastructure development while the remaining 30 per cent was used for private housing development.

While some may see this approach as akin to government-business collusion, we should recognise the public-private partnership model for what it is and acknowledge its benefits in bringing in private funds, efficiency and innovation.

With more than half of the land earmarked for the hub in private hands, there is much potential for private participation. For example, rather than having the government resume all private land, owners could be offered incentives such as concessionary land premiums to develop theses areas for I&T use.

As a prerequisite, however, they would have to secure commitments from leading I&T enterprises, which would be subject to government approval. This would reduce the burden on public finances and offer an alternative channel to complement the government’s

efforts to attract investment.

Even though the government has promoted a policy of non-interventionism for decades, Hong Kong has thrived as a laissez-faire economy. Even today, many believe Hong Kong’s qualities speak for themselves and don’t need to be promoted. In contrast, its competitors are pulling out all the stops to attract investment. Singapore, for example, was prepared to lower

its corporate tax rate for foreign companies to zero per cent.

Moreover, statistics suggest that Hong Kong is falling behind in global economic competition. As a percentage of GDP, Hong Kong has the lowest research and development expenditure and the smallest manufacturing sector among the four

“Asian dragon” economies. Therefore, it can no longer afford to rest on its laurels and wait for business opportunities to come knocking.

As competition for investment intensifies globally,

tax incentives and concessionary land prices have become points of parity. To establish points of difference, the government should provide tailor-made incentives to meet industry- and company-specific needs.

More importantly, firms need to be offered a compelling business proposition, such as market access and significant opportunities from harmonisation within the Greater Bay Area. The recent

memorandum of understanding between the Innovation, Technology and Industry Bureau and the Cyberspace Administration of China to promote cross-border data flows can be one such selling point.

Public tenders are the usual method for government land sales. Besides being relatively simple, they are objective and competitive, as tenders are awarded to the highest bidder.

However, with some of the

highest land prices globally, it would be a tough sell to attract leading I&T enterprises when local authorities across the Shenzhen River are willing to offer below-market land prices. Instead, the government can deploy various land allocation methods depending on the stage of development of the I&T ecosystem.

Considering the need to attract leading I&T enterprises during the early stage of development of the hub, the government should use direct land allocation to facilitate negotiation and devise custom terms. However, a general policy framework should first be created to ensure transparency. Subsequently, restricted tender could be used to recruit complementary enterprises in the industrial chain.

With the I&T cluster taking shape, this approach can be used to bring in unique concepts and designs. Eventually, as the San Tin Technopole establishes its reputation as an

international I&T hub, land could be sold through open tender to maximise revenue.

To create new impetus for growth, the government has resolved to diversify the economy. This is a welcome change in policy, but more needs to be done in practical terms. While the old ways have served Hong Kong well over the years, we should also have a forward-looking approach to match the futuristically named San Tin Technopole. After all, change begins in the mind.

Ryan Ip is vice-president and co-head of research at Our Hong Kong Foundation

Jason Leung is a researcher at Our Hong Kong Foundation