[ad_1]

Introduction

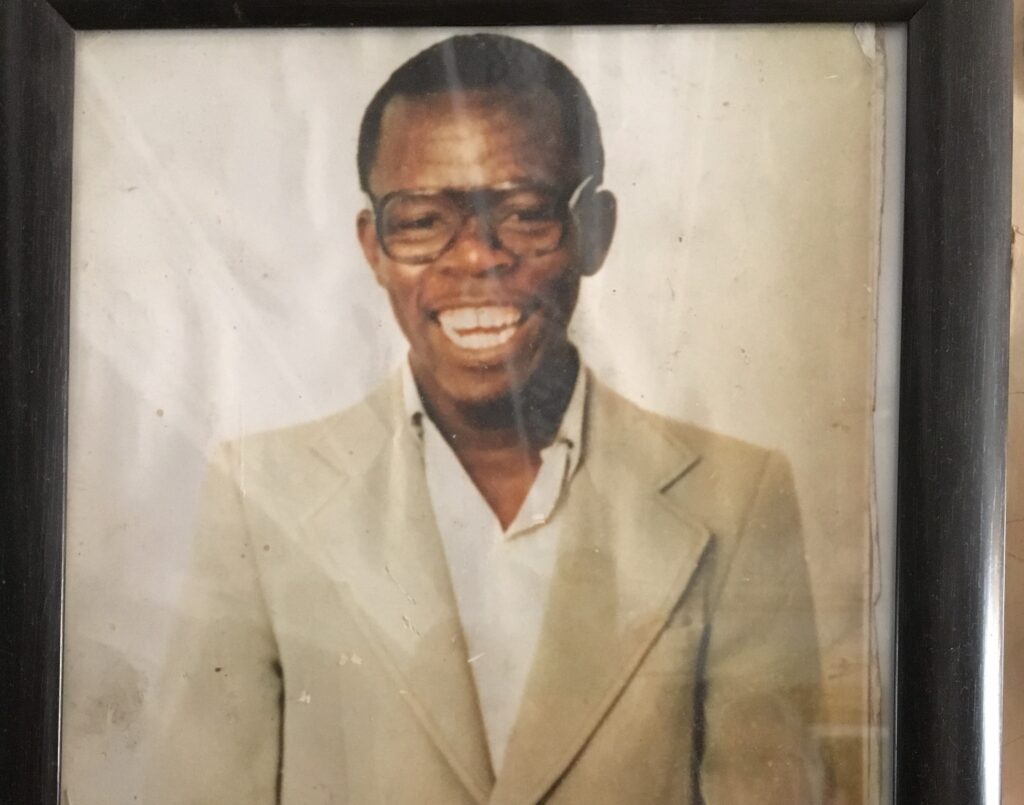

The six years Khulu Radebe spent on Robben Island were critical in his journey to become a comrade. Still a teenager when he first set foot on the notorious prison in 1978, he was one of the island’s youngest prisoners. Entering as a young firebrand, he and other members of the “June 16th generation” adopted a more confrontational stance than older leaders like Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu to combat the almost unimaginable abuse they endured from warders and prison authorities. They took these stands from the moment the guards loaded them onto the truck that took them to the place that would be their home. Khulu’s defiance also led him to help organize and carry out hunger strikes to protest the guards’ constant strip searches and drenching of the prisoners’clothes during the midst of winter.

It was very cold on the island, which is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean. It was often below freezing. I pity the slaves who were taken across the ocean without proper clothing. That is one reason why many of them died.

The warders used to wake us up in the early hours of the morning. ‘Strip search,’ they would say. They would usually wait for an exceptionally cold day when it was also raining. Then they would make us stand naked outside and pour freezing water over us.

We would stand there for hours while they were checking everything in the cell. They said that they were looking for banned material, including banned literature. They used this procedure when searching for knives or other dangerous weapons in the criminal section. People who carried sharp objects, handmade knives or spoons inevitably came from the criminal side. We were political prisoners – not that they ever called us that. They labelled us ‘security prisoners’.

Many people developed chest problems and asthma as a result of the damp floors during these searches. To me, it was just harassment. If they found something, you’d be charged again. They would open a new case against you and you would get a further sentence. You would be put through a trial on the island or on the mainland, depending on how serious the charge was.

Sometimes guys would get caught with banned material, usually part of the secret teaching materials and methods developed for education on the island. Teachers would usually write on the ground; or they would talk to you quietly while moving at your pace. There was also a system whereby you could be taught through notes written on toilet paper. Teachers might cover Marxist and Leninist concepts, like the history of dialectical and historical materialism, on toilet paper, for example. You’d read through them before using the toilet paper for its intended purpose. We were taught an art of remembering so that you wouldn’t carry anything incriminating on you.

The guards would be frustrated when they didn’t find anything and would come in with their hosepipes. They would pour water on our blankets and on our clothes, and drench everything in our cells. ‘You’re a fucking …,’ they would swear at us as they were doing it.

They were trying to break us so that when we got off the island we wouldn’t partake in any political activities.

It was very heavy to deal with, but we just kept quiet at first.

We did talk about these experiences with Nelson Mandela, who was the head of our committee. He and the other leaders in the Makhulu Span (team), or ‘Senior Group’, were on their own in B

Section, which had the most privileges. They helped us whenever we had to deal with issues of school bursaries, school books, or whatever other nitty-gritty matters we were trying to sort out. They would, in effect, negotiate for us. We would even send grievances against the authorities to the committee. They were our voice in such interactions. Around 1983, the authorities adopted a policy that said prisoners from different sections could not meet with each other.

I don’t know why they did this. It appeared to be an attempt to separate us from each other. Prisoners who came to the island after our release told us that the policy didn’t work and the authorities abandoned it in 1984 or 1985.

We started by engaging with Mandela, Govan Mbeki and the Makhulu Span about the strip searches, and they assured us that they were already handling the matter.

‘But you are not handling it,’ we replied. ‘You’re not handling it in the right way, because the harassment is continuing. The other issues – around school – are fine.’

‘No, listen, young guys, comrades. We are talking to them,’ they answered. ‘We’ll find a solution to these problems.’

We younger prisoners trusted the members of the Makhulu Span. But we young boys who were in cell block F were so unhappy about the strip searches that we came to a firm conclusion and took a decision: ‘You know what? If we don’t stop this nonsense now, no one is going to stop it. These older ones are being crazy. They will say something to the officials again, but nothing will change. Let’s embark on a hunger strike. Let’s start fighting.’

Normally, it was the Makhulu Span from B Section who called a hunger strike. Everything was done through the upper structures. There were also structures responsible for sports and politics, and everything was properly coordinated in a collective manner. This time, we told the Makhulu Span that we were fed up. They could go on eating. We were going on strike.

We had taken this decision in the communal section after several months of waiting for change. Even there I was not in control – I was just one of the fighters. We mobilised the whole prison, starting with F Section. Then it was D Section, E Section, then C. When it came to B Section, we compromised: ‘They must eat because they’re old, they’ve got medical conditions,’ we said.

The strike went on for more than a month. We refused to work since we were not eating and just stayed in our cells. We were not going anywhere… The warders thought we were crazy. They didn’t know that the secret of the hunger strike’s success lay in our anger. Nothing will make you eat when you are angry. When somebody gives you food, you say, ‘No, I am fine.’ We were angry and bitter, and had made our decision, once and for all, not to eat.

The guards would put food out in front of us and offer it to us. They would bring chicken straight to your cell on weekends. They would braai it in the kitchen and bring it to you. The smells. Wow! Yet we were never tempted, because we knew why we were fighting. Instead, we told them that we did not want their cooks in the kitchen anymore; and that in future we would want only our own guys to do the cooking. This was the latest in a long list of demands that went well beyond the call for an end to strip searches.

We demanded that they stop harassing us and listen to our grievances. We told them that we wanted sports privileges. Most of the guys who were grounded in D group had not advanced far in their schooling and needed to go ahead with their education. We in F Section also wanted to go to school.

Some of the guys collapsed while we were on hunger strike, and the authorities would try to give them a glucose drip for energy. They refused. ‘If Oliver Tambo tells me to accept the drip, I will do it,’ they would say. ‘If that order comes from Lusaka, I will do it. Don’t bring the order verbally. It must be written and signed by Tambo. Then I will do it. Otherwise, no.’ They were truly the ‘tried and tested’ participants of that strike.

Our struggle led to a victory. In the end the authorities stopped the strip searches and agreed to all of our demands. We gained privileges for sports like tennis. We had asked to access books we chose ourselves at the prison library. That was agreed to as well. Finally, they gave us enough encyclopaedias to fill a barge.

Excerpt from Comrade King by Khulu Radebe and Jeff Kelly Lowenstein, all rights reserved. Comrade King is published by Jacana Media. The e-book can be purchased by going to: Amazon.

[ad_2]

Source link