[ad_1]

In November 2013, Xi Jinping, in his first leadership year, convened a plenary Communist Party economic meeting and unveiled an ambitious reform plan (the so-called 60 Decisions) that included giving a “decisive role” to markets and pruning back the state sector. Nearing the 10th anniversary of the Third Plenum and those Decisions, most are still to be implemented. Without those structural reforms, systemic challenges have grown, including crushing local government debt, an ongoing property sector crisis, continued addiction to investment projects for GDP growth, and falling confidence among both domestic consumers and businesses and foreign investors. Leaders and economists hint that macroeconomic stress is necessitating a renewed push for reform. As of the second quarter of 2023, the rhetoric and pronouncements have started to turn more practical, but concrete actions that have been taken thus far are not sufficient. Must-see improvements include economic research and information openness, no further crackdowns against foreign companies, and improved access to credit for private companies.

China’s Macro Story: Revisiting the Reform Trajectory

The premise behind China Pathfinder is that Beijing’s pursuit of market reform and liberal economic norms is responsible for both China’s growth and its embrace by the global economic ecosystem. The role of marketization in driving China’s growth since 1978 is well documented. Since launching in 2021, our China Pathfinder research has identified a stall in China’s market reform progress, which is at least partly responsible for the growth slowdown now evident.

That failure to reform is bearing bitter fruit as China’s economy endures a major structural slowdown that is difficult to ignore. Business investment is weighed down by an unresolved property crisis, government stimulus is hobbled by overleveraged local finances across the country, and long-standing dependence on exports is provoking a trade pushback abroad. Household consumption—the long-awaited driver of China’s future growth—has not bounced back strongly from the pandemic. Expecting households to “dare to consume” when their children have trouble finding jobs post-graduation, their housing values are falling, and their returns on savings deposits are shrinking implies a misunderstanding of human nature.

Until Q2 2023, private Chinese and foreign commentators were surprisingly consistent in arguing that China’s poor 2022 performance was a cyclical problem caused by COVID-19, and that the economy would soon revert to pre-pandemic growth levels of above 5 percent for years to come. Authorities issued Q1 results in striking distance of that (4.5 percent year-over-year) but appeared to fudge a number of statistics to do so. The Q2 results released in July reinforced concerns about data reliability, even while they told a story of faltering growth. While the GDP figure itself was high due to the previous fudging and weakness of 2022—at 6.3 percent—that number was lower than expected.

The magnitude of the headwinds confronting the economy has also sparked a new wave of public discussion in China, suggesting that the taboo on admitting problems in China’s economic trajectory was breaking down. Observable developments in the marketplace reflected the shifting fundamentals: foreign direct investment inflows reversed, the value of China’s currency fell, the central bank cut interest rates, credit growth slackened, unemployment rose, and consumer and producer inflation metrics fell, with producer prices falling at the fastest rate since 2015. These facts substantiate the anecdotal impression that the recovery was far short of expectations at the start of the year.

Comments from authoritative voices now acknowledge these structural problems. In a May speech, former National Development and Reform Commission official Xu Lin said that the current slowdown is not cyclical but structural. Similar arguments arrived in June from Yin Yanlin, former deputy director of the Office of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission, as he highlighted the increasing downside risks and weakening of the Chinese economy. Yin also recognized “significant unexpected changes” since the second quarter, leading to a need for caution regarding overly optimistic views on economic recovery. To address the economic slowdown, former officials like Xu Lin and Party-affiliated economist Jiang Xiaojuan emphasized the need for institutional opening up. Jiang called for a market-oriented, internationalized business environment and support for platform enterprises, while Xu stressed that expanding domestic demand and fiscal stimulus are insufficient and advocated for market-oriented reforms, rule-of-law governance, and protection of property rights, urging adherence to the route taken during China’s 1978 reform and opening policy.

Beyond the new round of discourse on the urgency of reform, the Party is signaling that “rebalancing” growth and seeking new development strategies have been on the radar for a while. In June 2023, Qiushi, a leading Communist Party journal, published President Xi Jinping’s March 2022 speech to Central Party School cadres, in which he touched upon the need for economic restructuring. He warned against relying on old growth drivers like excessive borrowing for construction, reckless investment, and scaling up projects. Directing attention to Xi’s speech now makes a potential change in approach to market reform seem like less of a sudden reversal, after a slew of policies since 2020 that had tightened government control over the economy.

With markets abuzz about the faltering recovery and no signs of the old policy tools of credit and investment-led stimulus, is it possible to say that Beijing is course-correcting and now steering down the difficult road back to decisively market-driven norms? While Beijing fell short in implementing the 60 Decisions, adjustment pain will be even worse now than it would have been a decade ago. As difficult as implementation is, the consequences of standing still are even worse, as China’s economic growth would only continue slowing in the next decade. Does China’s leadership believe that, or still harbor hopes that an easier solution can be found? We cannot know, but the structural economic slowdown that has resulted from inaction is already underway and may well force Beijing’s hand.

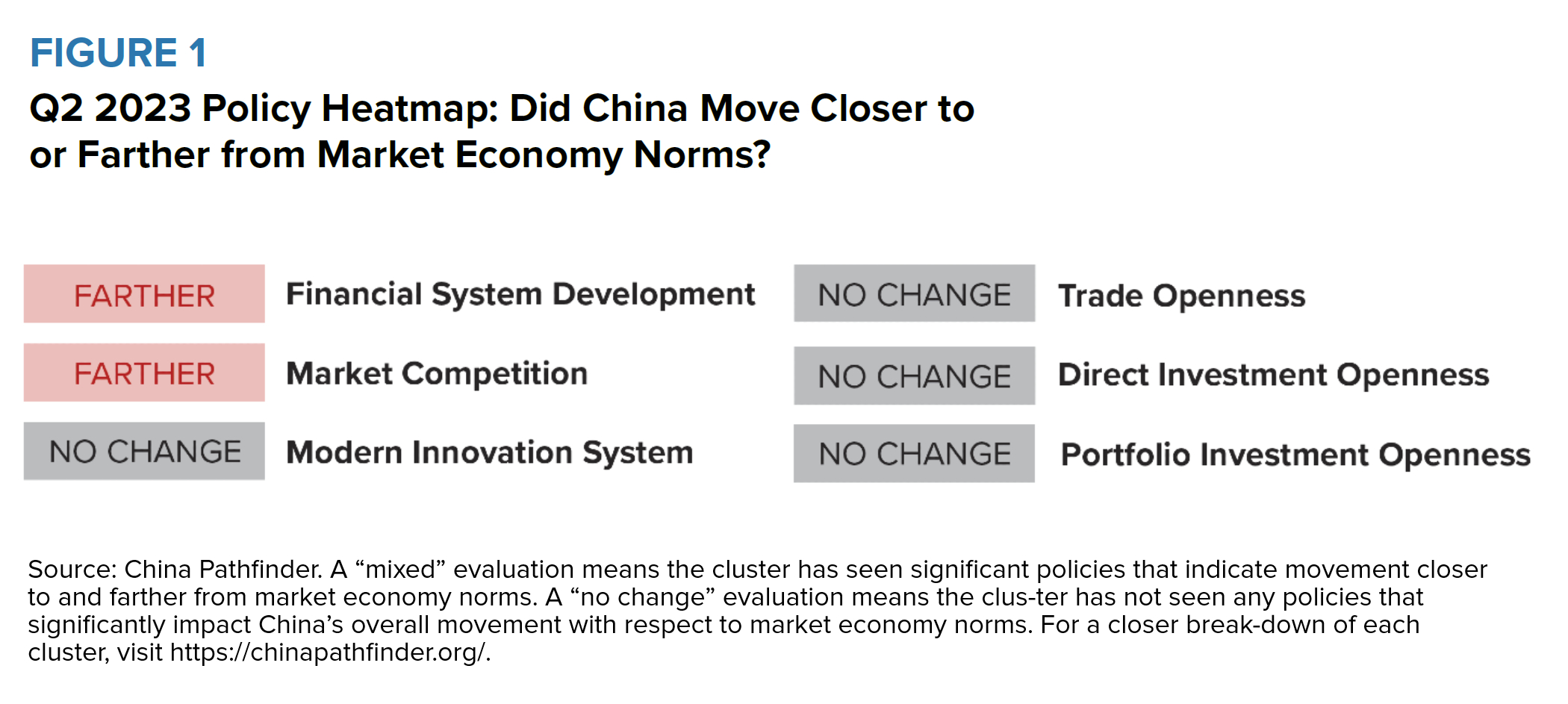

The willingness of important economists and former officials to acknowledge the structural slowdown and speak up in favor of reform is a positive signal. It is not enough, however, to indicate a meaningful change in policy (Figure 1Figure 1 reflects the direction of China’s policy activity in the domestic financial system, market competition, and innovation system, as well as policies that impact trade, direct investment, and portfolio investment openness. This heatmap is derived from in-house policy tracking that weighs and evaluates the impact of Chinese policies in Q2. Actions are evaluated based on their systemic importance to China’s development path toward or away from market economy norms. The assessment of a policy’s importance incorporates top-level political signaling with regard to the government’s priorities, the authority of the issuing and implementing bodies in the Chinese government hierarchy, and the impact of the policy on China’s economy.). Resolving the long-standing problem of local government debt calls for fundamental central-local fiscal reform, which is not in evidence. Macroeconomic headwinds and a lack of strong policy signals favoring reform have dampened investor sentiment. Beijing has been promising a welcoming environment, but foreign investors and companies are still awaiting follow-through such as shrinking the negative list for foreign investment. Meanwhile, the revision to the 2014 Anti-Espionage Law sent foreign companies scrambling to understand if and how their business-as-usual activities, such as collecting economic data, may be affected.

Financial System

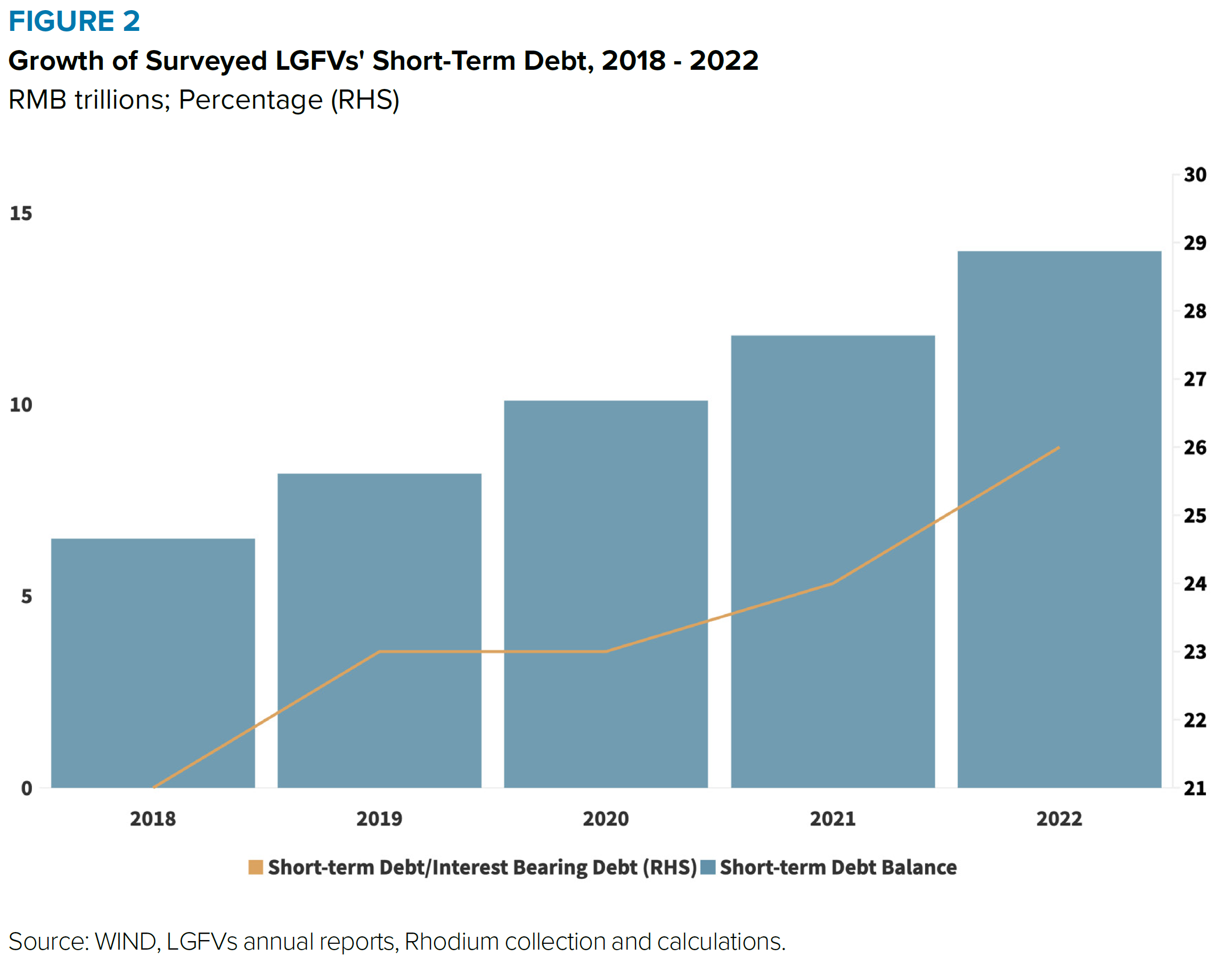

In Q2, mounting local government financing vehicle (LGFV) debt levels (Figure 2) and the absence of a concerted government effort to address the problem are the most critical areas to watch in determining China’s path toward financial system reform. At issue are the implicit guarantees for state and local government borrowers that distort the allocation of capital throughout China’s financial system. Beijing now faces a choice: place state, local government, and private firms on a more equal playing field, including the potential for default, or reinforce the special status of state-owned and local government firms. Though local debt is a long-standing problem, it has become more acute in recent quarters as local governments’ financial distress is rising.

Only about 20 percent of LGFVs have enough cash reserves to meet their short-term debt obligations and cover interest payments. The risk of LGFVs defaulting on publicly traded corporate bonds is growing. Localities are beginning to raise alarm bells, with some officials in Hohhot (Inner Mongolia) and Guiyang (Guizhou) openly declaring that those cities’ debt levels are unsustainable. More localities are likely to follow with requests for help. A central-level plan to tackle the LGFV debt has yet to be rolled out. Beijing does not appear to be taking a coordinated approach, though at the July Politburo meeting, China’s leaders promised to formulate and implement a comprehensive plan to reduce debt. In the meantime, China’s state pension fund recently advised asset managers to sell some bonds to reduce exposure to certain LGFVs, rather than increasing financial support to troubled localities.

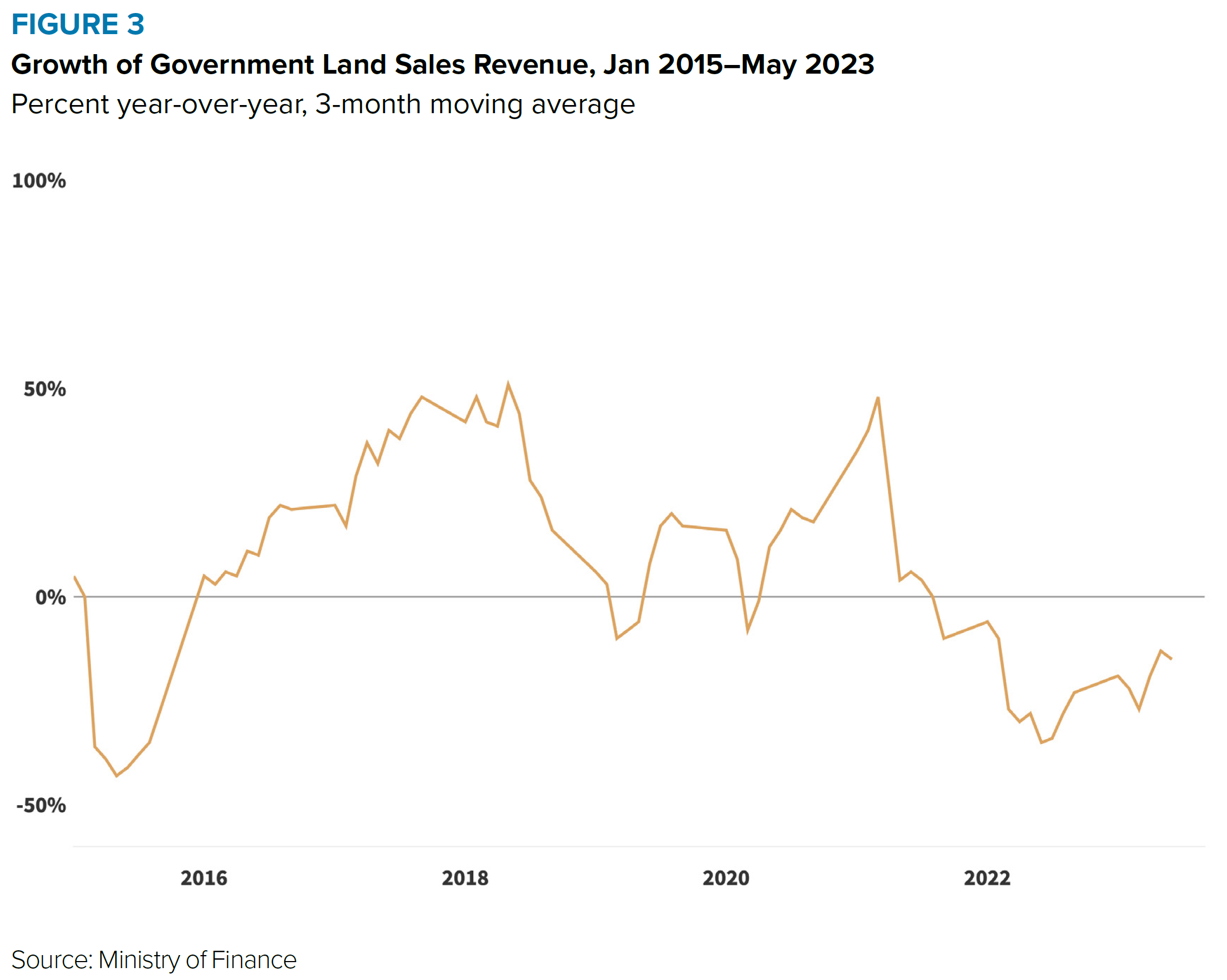

Continued property sector weakness in Q2 exacerbated the problem, with local government land sales revenues falling by 13 percent year-over-year in June 2023 after an even steeper drop-off in May 2023 (Figure 3). Local governments in China are responsible for the vast majority of government spending but keep only a small share of tax revenue they collect. Resolving the local debt issues, therefore, goes to the core of Beijing’s ability to use fiscal policy to stimulate the economy. But meaningful reform would entail turning away from investment-driven growth—a fundamental revamp of China’s growth model for the last 20 years—a step the government has been unwilling to take so far.

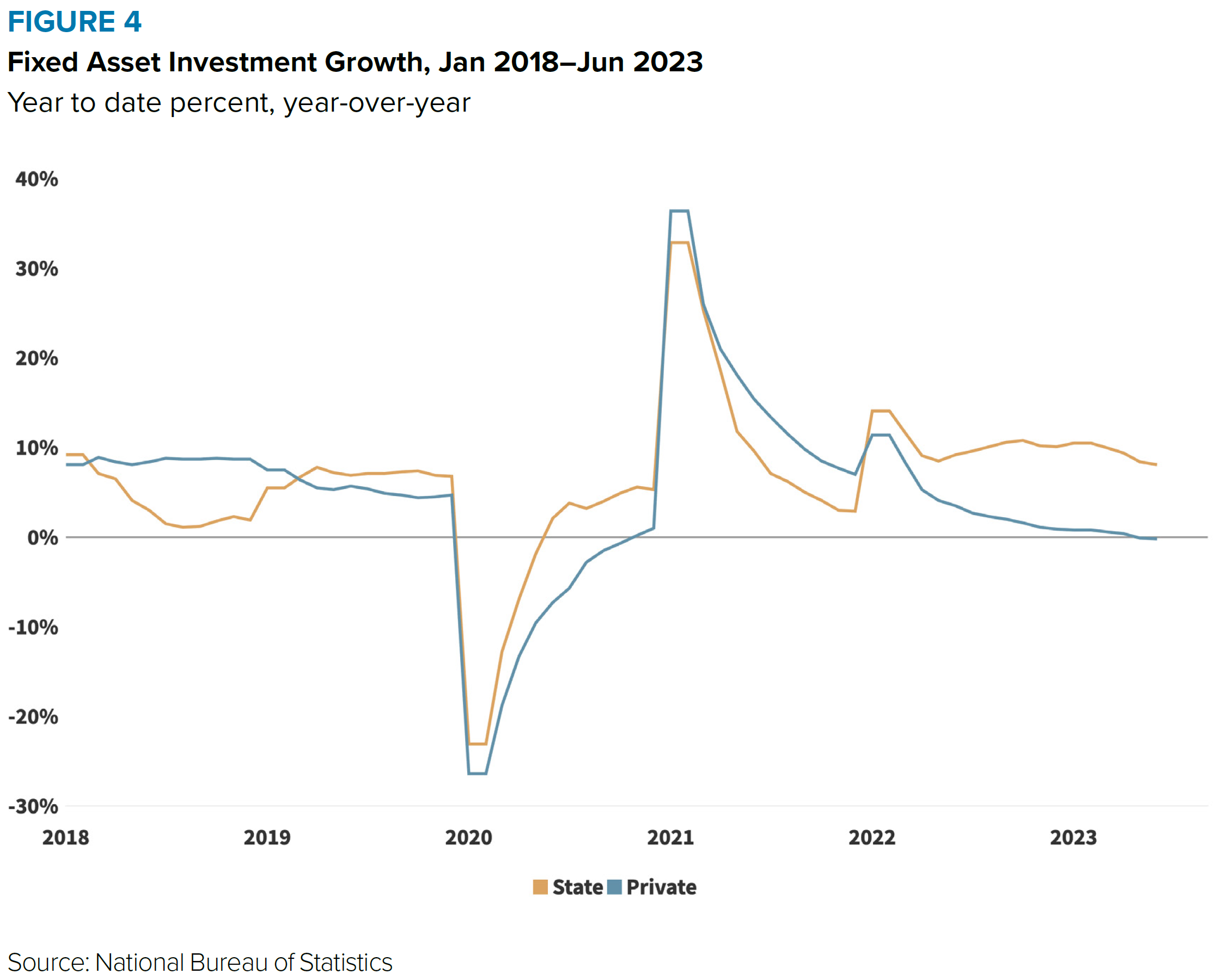

Meanwhile, reforms to the financial system that would improve private enterprises’ credit conditions and boost private sector investment have been promised, with little implementation. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and LGFVs still bear implicit guarantees, which distort credit allocation in their favor. As of June 2023, the gap between investment growth by private enterprises and SOEs increased to nearly 9 percentage points (Figure 4), with this year marking a rare circumstance in which state firms outpaced private sector investment. In Q2, an ongoing anti-corruption campaign in the financial sector likely contributed to increasing difficulties for private sector firms. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) oversaw the expulsion of ex-central bank deputy Fan Yifei and the former head of Exim Bank of China’s Yunnan branch, Dai Shihong, from the Communist Party.

China’s government has also cracked down on the financial sector’s high-paying positions in the last few quarters. In the latest move to limit Chinese investment banks’ high wages, CCDI pressure has prompted the country’s third-largest brokerage China International Capital Corporation to cut bonuses. Staff at CITIC Securities and Haitong Securities also reported salary cuts, and in some cases, a reduction in base pay for junior to mid-level bankers that could amount to 15 percent or more. These actions are likely to make loan officers far more conservative and perpetuate the preference to lend to SOEs instead of risk financing the private sector, since officers are unlikely to be rewarded for taking more market-friendly risks.

The quarter saw some incremental steps aimed at making foreign business operations easier. In June, the State Council rolled out new pilot measures for six of China’s 21 free trade zones (FTZs) and free trade ports. The measures are notable for further opening the financial sector, including remittance “without delay” of investments (e.g., dividends, capital gains, etc.) and allowing individuals and companies to use overseas financial services. Also surprising was the promise that the government is not allowed to ask for the source code of any software imported and distributed within the six FTZs. Actual foreign business operations within these FTZs will likely be slow to develop as these new regulatory regimes are tested.

Market Competition

For China’s economic recovery to gain momentum, private sector confidence—both domestic and foreign—must return, as private companies are key drivers of employment and new investment. But as has been the case over the last several quarters, reality is not matching the promises. From sudden raids and investigations into foreign firms to more rigorous implementations of counter-espionage rules, whatever goodwill Beijing has generated with its recent rhetorical charm offensive is in danger of being squandered.

Start with the amended Anti-Espionage Law, which went into effect on July 1. The amendment broadens the scope of targets for espionage to “all documents, data, materials, and articles” related to national security and interests, raising concerns about the potential abuse of power. Foreign companies fear the expanded scope could be interpreted in a way that restricts regular business activities since the definition of national security is left ambiguous.

Foreign business confidence was already shaky following raids on due diligence and consulting companies, including Mintz Group, Capvision, and Bain, earlier this year. In May, CCTV, China’s state television, dedicated 15 minutes to a prime-time segment accusing foreign countries of stealing information as part of a “strategy of containment and suppression against China.” A May editorial in the People’s Daily, the CCP’s official newspaper, warned foreign consulting companies that sharing information on China’s sensitive industries would be treated with “zero tolerance.” Beijing’s retaliation against Micron, a major semiconductor manufacturer, raised further concerns that geopolitical tensions outside of companies’ control will impact business conditions in China.

Keeping the spotlight on data security, Chinese regulators ordered SOEs and domestically listed firms to strengthen checks when hiring accounting firms and manage how information is provided to them to “effectively prevent” the risk of leaking. The ability of auditors to independently assess company data is a perennial pain point in US-China relations. If these security checks are overly stringent or used as a tool for political control, they could restrict the ability of independent accounting firms to provide accurate and unbiased financial assessments. This could undermine the credibility of financial reporting just when foreign and domestic investors need a reliable gauge to feel confident in their business decisions.

Mindful that buttressing business trust is key, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which has become China’s main regulator for all things digital (and was behind the crackdown on rideshare company Didi), launched a campaign against online “slander” and rumors that may harm the reputations of businesses and executives. While all governments struggle with misinformation, if not implemented carefully, the restrictions could hamper the flow of information and discourage open discussions of sensitive economic issues.

Watching for Signs of Market Reform in H2 2023

Evidence of China’s economic malaise is becoming impossible to deny for even the most optimistic observers. Since mid-June, analysts in international financial markets and global corporates have overwhelmingly abandoned the belief in a 2023 economic recovery and a return to pre-pandemic growth for China. This significant shift in market perceptions is reshaping investment flows. China’s currency has weakened as both FDI flows and portfolio securities flows are now reporting net deficits.

It is an encouraging sign that important economists and retired government officials have sufficient political room to publicly speak about the structural nature of China’s slowdown and call for economic reforms. Will their pleas prompt Xi to loosen the reins a little and choose restructuring and growth over control? The green shoots of structural market reform would be easy to miss amid moves to simply reassure foreign investors and marginally improve the business environment.

It would be unrealistic to expect dramatic reversals or sudden shifts in China’s economic policies, but here are three things we’ll be watching for in the second half of 2023 to see if China’s government is taking a more constructive path:

1. Information and data transparency

Between faltering growth and rising business skepticism, having a clearer view of economic sentiment has never been more urgent. Yet Beijing’s official line remains that bad news is fake news. The Q2 2023 GDP growth rate entailed data revisions that had no connection with reality. And Goldman Sachs recently found itself criticized by Beijing for downgrading outlooks for three Hong Kong-listed Chinese banks. Similarly, the China Securities Regulatory Commission met with law firms to limit the level of disclosure on China-related business risks in IPO prospectuses of Chinese firms looking to list overseas. With the CAC’s stricter rules for cross-border data flows, Wind, China’s biggest financial data provider, began restricting offshore users from accessing certain economic and company data. This July, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) added to the complexity of cross-border data regulation, releasing draft measures for the financial sector—the rules will require sensitive data to be classified using both the CAC rules and the PBOC’s own classification system. For Beijing’s reform signals to be treated credibly, it must allow candid discussion of China’s economy as it is, not as the government wishes it to be.

2. Foreign business climate

Beijing’s public messaging toward foreign businesses over the last few quarters can most charitably be described as convoluted. Appeals to foreign investors are followed by corporate raids; promises of deeper engagement in the global trading system are followed by new export controls. No wonder foreign companies, which seek growth and stability, are starting to look around for opportunities elsewhere. Just over the last few months Ford, LinkedIn, and Forrester Research have withdrawn or scaled back their presence in China. Seeking to moderate geopolitical risks, venture capital company Sequoia spun off its China business. Most recently, Morgan Stanley is in the process of moving 200 technology developers—one-third of the company’s China-based technologists—out of the mainland due to the country’s tightening data rules.

3. Private enterprise boost

China’s private sector remains scarred by the regulatory crackdown, zero COVID, and weak economic growth. Although Beijing has been vowing to improve its lot, there has been more talk than action, and even the publicly available data clearly show the weakness of China’s private sector. Total investment among private firms has fallen by 0.2 percent in the first half of 2023, while SOE fixed asset investment has grown by 8.1 percent so far this year. Consumer tech firms have been hit hardest, with leading firms cutting 11 percent of employees over the course of last year. Distortions in private sector financing are becoming unsustainable, with IPO approval rates, for example, strongly biased toward SOEs. This is partly a consequence of needing to list local SOEs to manage rising local government debts, but also a function of growing securitization of economic decision-making in the name of national security. In July, the Party Central Committee and the State Council released 31 different measures to support the private sector, but the reaction to the announcement has been muted or even skeptical. Firms want to see concrete actions. Changing incentives in the financial sector toward lending to private firms (such as moving away from relying solely on fixed assets as collateral) would be a meaningful step to reduce perennial favoritism towards SOEs.

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the China Pathfinder Advisory Council: Steven Denning, Gary Rieschel, and Jack Wadsworth, whose partnership has made this project possible. Niels Graham, Jeremy Mark, and Miles Munkacy were the principal contributors from the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

[ad_2]

Source link