[ad_1]

Twenty-one years ago, the British wine writer Andrew Jefford published The New France (Mitchell Beazley, 2002), bringing his discerning palate and formidable intellect to bear on that celebrated wine culture. Region by region, Jefford deconstructed the country’s terroirs, highlighting its wines and winemakers with wit and deft observation, for a vivid snapshot of the place in its time.

Often the most revealing section of each chapter was the one Jefford called “Flak,” the contradictions, controversies and paradoxes he couldn’t quite reconcile. It was an acknowledgment that parts of this ancient culture, bolstered by tradition, bureaucracy and pride, would elude him, even as it remained the source of some of the greatest wines in the world.

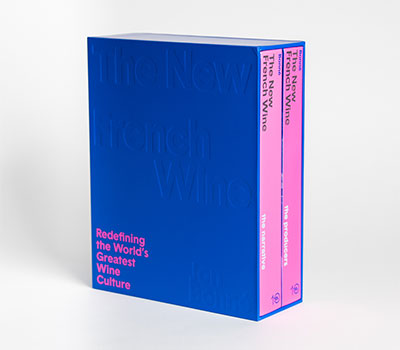

From the first sentence of his masterful two-volume set, The New French Wine, Jon Bonné embraces the flak. With that sentence—“C’est compliqué”—Bonné lays out his intention to lean into every contradiction, every paradox, every trend and principle, creating a portrait of the country in all its turbulence and vitality, a wine culture rooted in tradition, and straining to break free. His 864-page work, with arrestingly candid photographs by Susannah Ireland and charmingly retro map illustrations by Francesco Bongiorni, took more than eight years of research. Having traveled to 72 of the country’s 96 départements, clocking 30,000 km on its roadways, he has created a comprehensive picture of French Wine in its current moment.

In his 2013 New California Wine, Bonné performed a similar feat, chronicling a perceptible shift at the end of the Parker era, marking an inflection point and a trend toward diversity in California wine that is still evolving today. For The New French Wine, there’s considerably more heavy lifting.

Bonné lays out his subject in two volumes: The Narrative and The Producers. His producers volume—with more than 830 portraits—is arranged beneath two rubrics: “Names to Know,” or worthy additions to the canon, and “Benchmarks,” those legacy wineries that also seek to push the culture forward. “Change,” he writes, “is an inclusive force.” This half of the book alone is an invaluable resource for new wines to try. But the book’s heart is in The Narrative.

“Are the [French] appellations compatible with individual, personal expression?” Chablis producer Claire Naudin asks. Bonné find the answer is often no.

Like Jefford’s before him, Bonné’s narrative proceeds geographically, focused on the producers who are driving each region in its forward movement. He does this with an astute eye for the sort of details which describe the country à la minute, whether it’s the graffiti on a bench overlooking La Tâche, in the heart of Vosne-Romanée, or stuffed animals strung along the concrete tanks at Pétrus. That eye extends to the country’s changing landscape, economy, its political and social ethos, demonstrating how French Wine is more than just the product of a location—it’s the product of French culture, a mindset that both burdens and liberates. To his regional chapters he adds six interstitial sections covering patrimony, mythmaking, the rise and fall of the appellations, natural winemaking, farming, and, most critically, the climate.

Citing historic texts, documents, antique inventories and reports, Bonné makes it clear that it’s impossible to know France in its current zeitgeist without a thorough examination of what’s gone before.

Nowhere is this more true than in his examination of the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée system or AOC, the historic, multi-tiered hierarchy designed to maintain quality and preserve terroir for each major region in France. Bonné lays out a clear-eyed portrayal of the AOC’s historic merits and current shortcomings, portraying a system borne of idealism and grown into a bureaucracy of control, indolence, and restriction, or, in Bonné’s words, “an industrial-minded nanny state.”

He cites numerous examples of this calcification, quoting, for instance, Chablis producer Claire Naudin who asks, point-blank, “Are the appellations compatible with individual, personal expression?” Bonné reaches the uneasy conclusion that the answer is often no.

An emerging alternative for many has been natural wine. Bonné’s chapter “Observations of a Natural World” begins, naturally, with a lively rendering of the controlled chaos of La Dive Bouteille, the annual gathering of naturistes in Saumur. Bonné takes its measure as a kind of outsider, as someone who can recognize and appreciate the energies of the movement as he documents in vivid detail its shortcomings. Some of the chapter is devoted to defining what makes a wine natural, with long explications on sulfur use, on the constraints in the cellar, but also on flaws like volatile acidity, Brettanomyces, and goût de souris (mousiness).

But he spends just as much time exploring natural wine as an ideology, one that is prone to as much groupthink and snobbery as more established factions, so much so that wines in this cohort, despite obvious, literal flaws, are often considered beyond judgment because of the purity of their intent. Citing Althusser and the Salon de Réfùsés, Bonné thinks this itself a grand French tradition—or obsession, “a craving for solidarity, even in rebellion.” Those who rebel inevitably coalesce. But, he asks, “At what point does the natural vibration—wine following its own path, even if that path leads to darkness—deviate too far?”

The natural wine movement is at a crossroads, as it transforms into an institution, and Bonne’s depiction of that moment in time, along with numerous others, can be riveting. Like Jefford’s before it, this is a book that is destined to become obsolete; but it deepens our understanding of France and French wine in this moment.

The New French Wine: Redefining the World’s Greatest Wine Culture, by Jon Bonné (864 pages, Ten Speed Press, 2023, $135)

This story appears in the print issue of Summer 2023.

Like what you read? Subscribe today.

[ad_2]

Source link