[ad_1]

August 8, 2022

When will Sweden and Finland join NATO? Tracking the ratification process across the Alliance.

This post was last updated on March 30, 2023.

Finland has reached the finish line—while Sweden is still in limbo. With this tracker, the Atlantic Council team is keeping tabs on the countries that have ratified the amended NATO treaty to welcome two new members—and handicapping the political prospects for ratification in the countries that have yet to approve the Swedish bid.

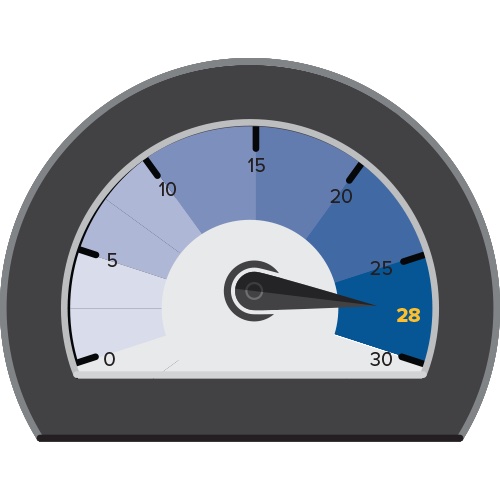

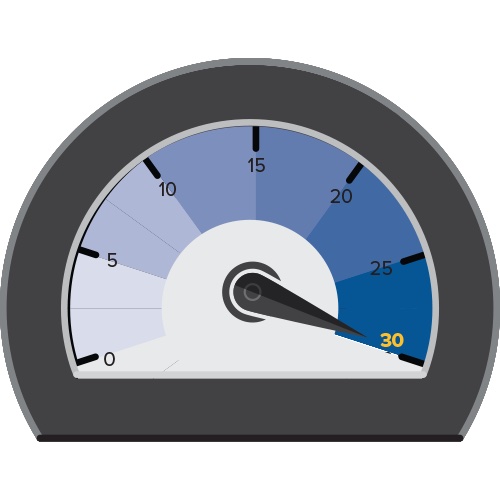

Turkey’s March 30 vote to ratify Finland’s membership—but not Sweden’s—makes it the final ally to approve Helsinki’s bid. Twenty-eight allies have done so for Sweden, with Turkey and Hungary the remaining holdouts. Below find what to expect from them in the coming months.

Current count: Number of NATO members that have ratified NATO enlargement…

…for Sweden

…for Finland

Timeline: NATO members that have approved Finland and Sweden’s accession, by date of ratification

Click the left and right arrows to move through the timeline

Map: Who has ratified Finnish and Swedish accession–and who hasn’t yet

Source: NATO Parliamentary Assembly

Cheat sheet: Expert intel on the next ratification debates to watch

TURKEY: As the door opens for Finland, approval of Sweden could take months or years

Erdogan’s decision to recommend approval by the Turkish parliament of Finland’s NATO accession prior to an upcoming parliamentary recess highlighted Niinistö’s visit to Ankara and marks an important milestone both for the Alliance and for Turkish efforts to coax Europe into closer cooperation against the the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a US- and European Union-designated terror organization. The decision brightens prospects that NATO will admit Finland by the Vilnius summit in July, adding a defensive bulwark along Russia’s northern border. It also demonstrates that Ankara’s approval depends on concrete counter-terror cooperation, rather than simple obstinance or electioneering. (If Erdogan is mugging for votes by delaying Sweden, is he sabotaging electoral prospects by moving Finland forward?)

Erdogan’s comments on March 18 indicate that progress for one aspiring member does not assure progress for the other. Sweden has yet to fully implement new counter-terror legislation that comes into effect on June 1, and in Erdogan’s words “has opened its arms” far more than Finland ever did to the the PKK and other anti-Turkish groups. The foreign ministers of Turkey and Sweden reportedly spoke March 18, though, and will meet again soon to assess progress. The timeline for Swedish accession will be longer than it was for Finland—far more likely months or years rather than weeks. Until PKK membership, fundraising, and propaganda action are curtailed (currently only violent acts by members of a terror organization are criminalized) in Sweden, the celebratory Niinistö visit is unlikely to be reprised by his Swedish counterpart.

—Rich Outzen is a nonresident senior fellow at Atlantic Council IN TURKEY and a former US State Department official.

Read what more Atlantic Council experts have to say about the state of play in Turkey:

HUNGARY: Its delays raise deeper concerns

On March 27, Hungary’s legislature approved Finland’s accession to NATO, 265 days after Helsinki signed the protocols to join. The vote moves the long-delayed process forward, but it still leaves unaddressed both when exactly Hungary will take up Sweden’s accession and why the Hungarian government has taken so long. After all, it took the first twenty-eight NATO members fewer than ninety days to ratify both Finland and Sweden’s accession. Hungary and Turkey have been the holdouts, and while they have shared this status, it is important to look at the differences in how Budapest and Ankara have handled the process. Doing so raises new concerns about Hungary’s approach to the Alliance beyond the specific issue of this enlargement.

The reasons Turkey has taken longer are well documented. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been quite clear on his major interests related to arms exports and in particular to Stockholm’s attitude toward Kurdish groups with alleged links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union (EU). And Turkey’s lengthy process toward ratification has strained Alliance cohesion and made happy its enemies, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin. That’s not a small deal.

Still, Turkey early on presented detailed arguments and conditions that allies could debate and sort out. In contrast, Budapest has been opaque on the reasons why it delayed ratification on Finland and continues to do so for Sweden. Given that other allies delivered more than six months ago, lack of time has long ceased to be an acceptable excuse.

The biggest concern with Hungary now is less that it might keep Sweden in limbo for a few more months before ratification, and more that it might do so without plausible arguments. Leaving no room for a meaningful discussion, Budapest impedes the basis on which the Alliance deals with critical issues and inhibits the bedrock foundation of democratic life itself: open and purposeful debate.

Read more from Petr Tůma, a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and career Czech diplomat:

Further reading

Mon, Aug 22, 2022

Sweden and Finland are on their way to NATO membership. Here’s what needs to happen next.

Issue Brief

By

John R. Deni

In response to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Finland and Sweden took the historic step of applying to join NATO. Both nations will bring modern capabilities that will help defend against malign actors. As Finland and Sweden’s membership is forthcoming, Alliance leaders, NATO watchers, and transatlantic security experts need to consider how to fully integrate the new allies, include them in operational plans, and best enhance defense of a longer border with Russia.

Tue, May 17, 2022

NATO Forward Forces Tracker

Trackers and Data Visualizations

By

In the lead-up to and following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the United States and NATO allies have taken numerous steps to bolster allied force posture in Eastern Europe. The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Transatlantic Security Initiative has been tracking it all. Check out its interactive table and charts to visualize the changes over time.

Image: Sweden’s Foreign Minister Ann Linde and Finland’s Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto attend a signing ceremony with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, signing their countries’ accession protocols at the alliance’s headquarters in Brussels, Belgium July 5, 2022.

[ad_2]

Source link