[ad_1]

While eurozone GDP was down in Q4 and Q1, it isn’t a mystery why its stocks are up.

After Eurostat revised down the eurozone’s Q1 GDP Thursday, it appears the monetary union’s long-awaited recession may have finally arrived—at least using one common definition. But this isn’t investors’ cue to run for the hills. For stocks, it seems mostly like very old news.

After the eurozone’s Q4 2022 GDP declined -0.1% q/q, recent downward Q1 2023 GDP revisions in Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany and Greece flipped the currency bloc’s Q1 growth from a 0.1% q/q initial growth estimate to a -0.1% contraction.[i] While two back-to-back quarterly declines are often considered a recession, that doesn’t make it formal. The responsibility for declaring recession belongs to the eurozone’s official arbiter—the Centre for Economic Policy Research’s Euro Area Business Cycle Network (EABCN)—which hasn’t weighed in yet.

Like the US’s National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee, EABCN’s committee considers broad criteria. Indeed, Q4 and Q1 GDPs’ -0.1% q/q downticks—the shallowest possible two-quarter drop—may not qualify, at least judging by EABCN’s latest pronouncement. In March, they found: “real GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2022 halted, but did not turn significantly negative, as a large drop in private consumption and investment was offset by a similarly large reduction in imports. The output growth pause contrasts with a continued robust expansion in employment, especially in the service sector.”[ii] Whether a second quarter of “output growth pause” constitutes recession or not is unclear—we will just have to wait for those fine folks to decide. Notably, US GDP endured a bigger contraction in Q1 and Q2 last year, and the NBER didn’t deem it one.

Then too, there was a lot of country-specific dispersion, which we think makes it inaccurate to say the whole bloc is in recession. One way to see this: In every EABCN-deemed European Monetary Union (EMU) recession since 1995, Germany and France—the two largest “core” euro countries—both contracted.[iii] This time around, while German GDP fell in Q4 and Q1, France’s rose. So did Belgium’s and Spain’s. All told, 16 of 20 eurozone countries grew in the last two quarters.

Meanwhile, German recession isn’t new news. Two weeks ago, Germany’s federal statistics office previewed Eurostat’s mild contraction reading. This comes after recession warnings since late 2021, making Germany’s dip one of the most expected economic potholes ever.

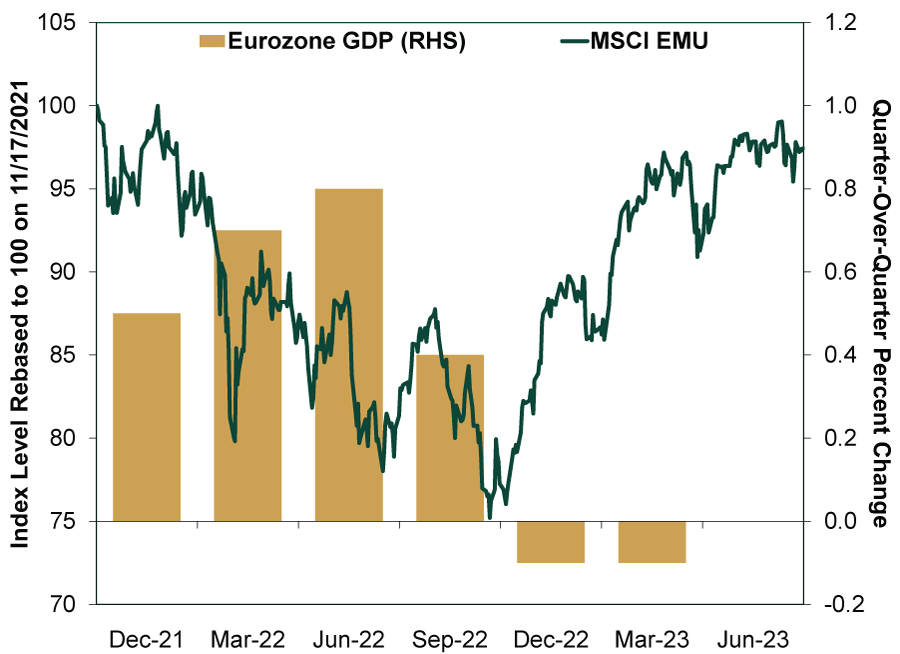

At this point, any recession declaration would come well after the fact—and following widespread anticipation last year. With Q2 wrapping up, it would be backward-looking and late-lagging, which we think is of little consequence for forward-looking markets. The MSCI EMU Index (of developed-market eurozone stocks) illustrates this beautifully, in our view. (Exhibit 1) It is up 29.6% in euros since its September 29 low—before recession supposedly started—outpacing the rest of world. And for the weaker nations specifically—e.g., Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany and Greece—their stock markets are all up more than that. (Note: Greece is in MSCI’s Emerging Markets, which the EMU Index excludes.)

Exhibit 1: Eurozone Stocks Moved Ahead of GDP

Source: FactSet and Eurostat, as of 6/9/2023. MSCI EMU returns with net dividends in euros, 11/17/2021 – 6/8/2023, and eurozone GDP, Q4 2021 – Q1 2023.

It seems likely to us markets priced eurozone recession—if it is that—in advance and are now looking further ahead. In our view, this is a textbook example showing how stocks, once again, are the best leading indicator.

[i] Source: Eurostat, as of 6/9/2023.

[ii] “The Latest Findings of the CEPR-EABCN Euro Area Business Cycle Dating Committee (EABCDC) – March 2023,” Refet Gurkaynak, John Fernald, Evi Pappa and Antonella Trigari, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), 3/29/2023.

[iii] Source: Eurostat and CEPR, as of 6/9/2023.

[ad_2]

Source link