[ad_1]

William Jones recalls that as a teenager in Memphis, Tennessee, Black police officers would break up pickup football games with friends when a white neighbor called to complain, often inflicting physical punishment in the process.

“And a lot of times, it was the Black officers who beat us worse than white officers,” Jones, 48, said.

So, when the images of five Black officers flashed on his television screen as the ones who allegedly beat Black motorist Tyre Nichols during a traffic stop on Jan. 7, Jones did not flinch.

“I was not surprised at all,” Jones, a high-security government worker, told NBC News. “Some of these officers get behind their badge, and they forget who they came from. They really believe in blue lives matter. Some of these Black officers are good guys that came from rough neighborhoods, too. But I have seen some of them take that power — lots of them — and misuse it. They didn’t come to my neighborhood and pull no cats out of trees. They came over when we were little boys, 13, 14 years old, and roughed us up. And for no reason.”

Jones and other Black Memphis residents have shared a range of reactions to seeing five Black faces as the alleged perpetrators of Nichols’ fatal beating with NBC News. Nichols, 29, died three days after the beating. Their reactions align with data about the city’s rate of police using force against Black people. According to a 2021 report on city data by TV station WREG, Black men were seven times more likely to experience police brutality than their white male peers.

“I can’t be surprised because it’s a predominantly Black part of town with Black officers patrolling,” said Barbara Johnson, 75, and a grandmother. “The relationship with Black people and the police is not very good. Black or white officers, it’s us against them. There’s this mistrust. Period.”

Brian Harris, 44, who is running for city council in the district where Nichols was killed, said the relationship between Memphis’ Black community and law enforcement is deteriorating, with this case a touchstone for even more discord.

“I’ve seen it shift over the years,” Harris said. “And that shift has come in part because policies have been relaxed as far as the officers we onboard. A couple of years ago, they dropped the 60 hours of college credit requirement down to just having a high school diploma, which changed the dynamics of those coming in. That was due to recruiting purposes.

“Still, I have never seen anything like this. When it comes to Memphis and Black officers and Black-on-Black confrontations …this is totally new,” Harris said. “But if you look at the history of Memphis and race relations, we’re oppressed, especially Black men. And to know that Black officers who took an oath to protect and serve turned on their own people … it’s just unacceptable, shocking and disappointing.”

Nichols’ mother, RowVaughn Wells, said in a news conference Friday with attorney Ben Crump, “I want to say to the five police officers who murdered my son, you also disgraced your own families when you did this.”

Memphians have endured officer-involved shootings of Black men in the past. Martavious Banks survived multiple gunshots by an officer during a traffic stop in 2018. In 2015, Darrius Stewart was shot and killed by a white officer during a traffic stop in the Hickory Hill section of Memphis, where Nichols was beaten.

“But this feels a bit different than everything else that we’ve seen,” said Todd Harris, a 25-year Memphis resident who works in banking. He said a police officer friend alerted him of Nichols’ death before it was made public.

“I was kind of surprised because being beaten to death is so extreme,” Harris said. “That’s more intentional than shooting the person. But I was even more surprised that he was beaten to death by five Black men.”

The circumstances, he said, have prompted conversations to be less about race and more about power.

But the issue is less complicated to Frank Johnson (no relation to Barbara Johnson), a Memphis native, school board member and activist, because he views the beating from a historical context.

“White supremacy has always had Black faces to carry out their deeds,” Johnson said.

For Carla Griffin-Crouthers, Nichols’ death signals a broader safety concern. “I used to go to the ATM and gas station at night without fear,” she said. “But now? No? Crime is surging and then you have the police who are supposed to protect you who are doing the opposite.”

She said she did not have “the talk” about how to interact safely with police with her 27-year-old son when he was a teenager, but “ I have since he’s become a young man. And sometimes, even that’s not enough.”

Some people, like Griffin-Crouthers, commend the police department for “acting swiftly” and firing the officers and then indicting them, although it was almost three weeks after the beating.

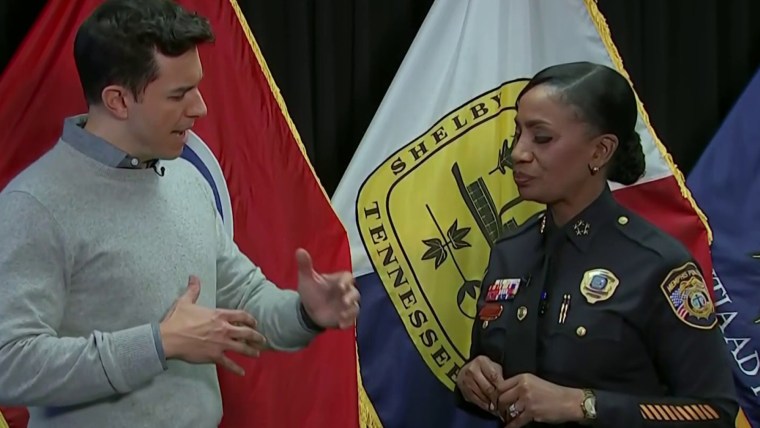

Memphis Police Chief Cerelyn Davis said to ABC News that the beating would only harm trust-building between police and Black communities in Memphis and elsewhere. Davis also acknowledged Friday to NBC News that the officers’ behavior at the traffic stop did not follow “police protocol.”

“I’ve been in business for 36 years, and a lot of the aggression and the approach [of the officers] was over the top,” she said.

Frank Johnson, however, said, “The only reason we know Tyre’s name now is because the activists in this city would not let his name go.There’s a whole lot of stuff going around saying how our police department got it right. No, they didn’t. They had to be forced to do this.”

Many Black residents in Memphis, Jones said, believe had the officers been white, a case would not have been created against them.

“No way,” he said. “That’s the history of Memphis. And that comment goes back to a lack of trust of cops, Black or white.”

Added Todd Harris: “Beating that man to death is a breach of trust — and just one more reason for there to be angst between the minority population and the police department.”

[ad_2]

Source link